Filippo Brancoli Pantera is a photographer whose work emerges at the intersection of visual inquiry and cultural reflection. He holds a degree in Cultural Heritage from the University of Florence (2004) and a degree in Cultural History from the University of Pisa (2025); in parallel, he studied stage photography in Milan (IED, 2005) and documentary photography in New York (International Center of Photography, Director’s Fellowship 2009). Active in the field of landscape photography, he has worked across territories in France, Italy, and Switzerland, collaborating with local institutions and exhibiting his work in exhibitions and books (Toscana Interiore, NPS, 2020; Le Beauvaisis, Diaphane, 2022). Since 2020, he has been developing a body of work that sees ritual action and the contemplation of recurring subjects as a way to transform the act of photography into a moment of heightened awareness of the surrounding world, seeking to connect everyday experience with that of ritual.

For limited edition prints (5 editions + 2 ap), please contact:

Filippo Brancoli Pantera -> filippobrancoli@gmail.com

or:

Galleria ConsArc

Switzerland

https://galleriaconsarc.ch

galleria@consarc.com

+41 (0) 91 683 79 4

Via Gruetli 1 CH-6830 Chiasso

or:

Riseart gallery

Selected exhibitions/publications/BIO

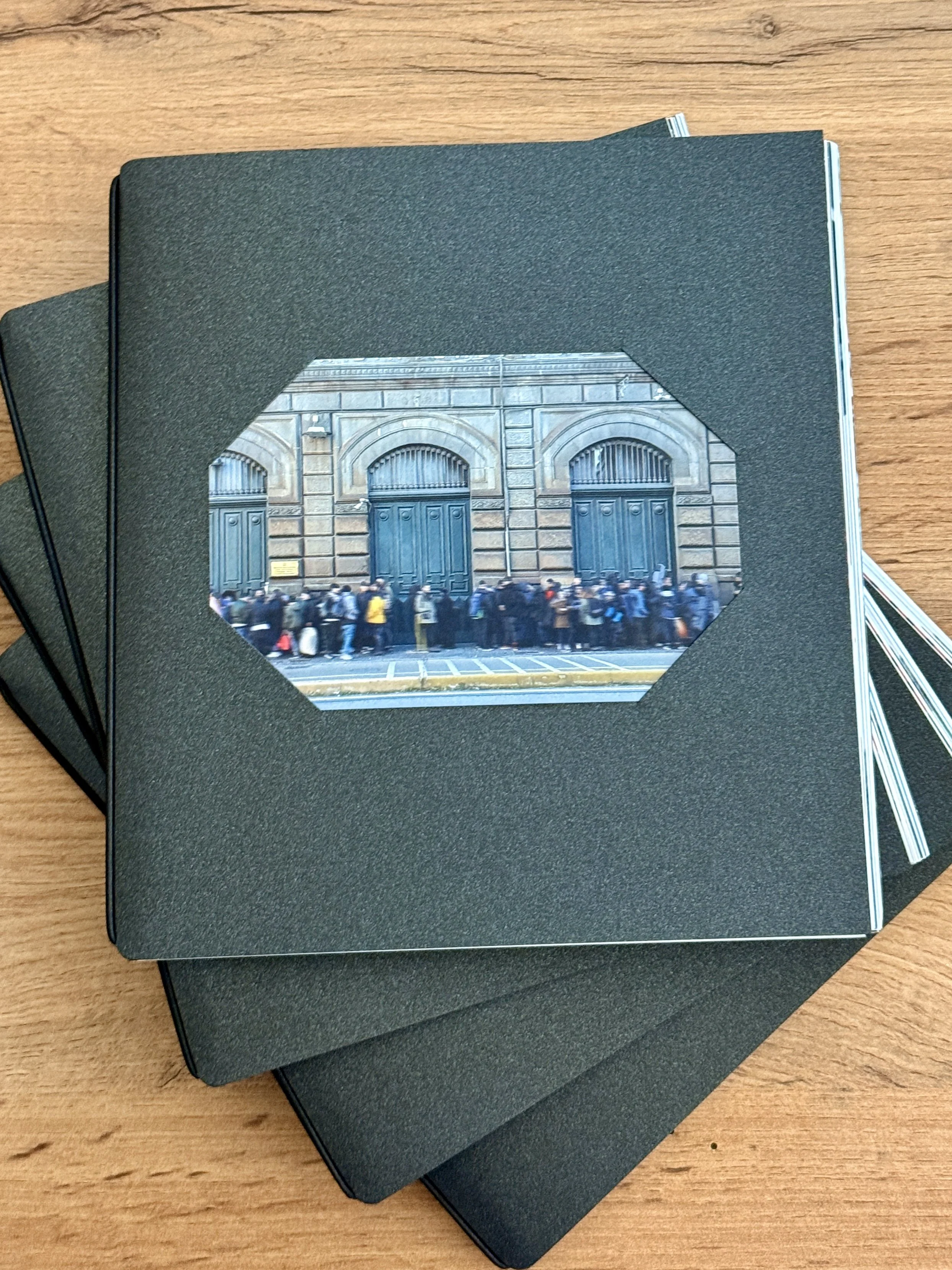

Artphilein Library - Lugano (CH)

with Veronica Barbato (images)

and

Filippo Brancoli Pantera (critical essay)

2025

Le Beauvaisis

book

Diaphane Edition, 2023

Le Beauvaisis

Exhibition

(Hermes, Oise, France), 2023

Tappeti Volanti

Festival del Possibile (Lucca, Italy), 2021

Exhibition Tappeti Volanti @ Festival del Possibile (Lucca, Italy) 2021

Rurban Corsica

avec Lola Reboud, commissaire Marcel Fortini

(Bastia, France), 2020

Rurban Corsica @ Centre Culturel Una Volta (Bastia, France) 2020

Toscana Interiore

book

NPS Edizioni, 2020

Book publishing Toscana Interiore

2019

Group Exhibition @ Photolux Festival (Lucca, Italy)

Artist residency @ Diaphane (Clermont de l’Oise, France)

2018

Group Exhibition @ Arles Voies Off (Arles, France)

Artist residency @ Centre Méditerranéen de la Photographie (Ville di Pietrabugno, France)

2017

Personal Exhibition @ Cons'Arc (Chiasso, Switzerland)

Group Exhibition @ OnArte (Minusio, Switzerland)

Into the Landscape

Galleria CONSARC

(Chiasso, Switzerland) 2017

Into The Landscape @ Galleria Consarc (Chiasso, Switzerland) 2017

2014

Personal Exhibition @ Fondazione Museo Lindenberg (Lugano, Switzerland)

Group Exhibition @ Maxxi, collettiva con Documentary Platform (Roma, Italy)

2013

Personal Exhibition @ Fondazione Banca del Monte (Lucca, Italy)

2012

Group Exhibition @ Fotografia Europea, collettiva Progetto QD (Reggio Emilia, Italy)

2009

Group Exhibition @ International Center of Photography (NYC, USA)

2008

Personal Exhibition @ Dak'Art, Biennale Arte Contemporanea (Dakar, Senegal)